🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

On Swiss tourism websites, it is not uncommon to see reference made to Switzerland’s centuries-old bread-baking traditions and the two-hundred-plus types of bread the country offers to the modern-day visitor.1 “Centuries” is no exaggeration, as the oldest evidence of bread—dating from 3500 BC—reportedly comes from Switzerland.2

Nor are Swiss breads just for tourists. According to one website, the average Swiss resident consumes over one hundred eight pounds (forty-nine kilos) of bread per year,3 compared to about one-third that amount annually (seventeen kilos) for the average American.4 (Americans help make up for their inadequate bread intake—by European standards—by keeping over thirteen thousand doughnut shops in business.5) Unfortunately, much of the Swiss consumer’s bread consumption appears to be in the form of variations-on-a-theme yeast breads made solely or primarily from refined white flour. Enticingly displayed in grocery store bread aisles and bakeries and even promoted in “traditional food” museums,6,7 breads such as the braided Zopf and raisin-studded brioche—once intended only for Sunday or special occasion use8—now seem to be easier to obtain than formerly “everyday” breads such as traditional sourdough rye.

BREAD THEN. . .

As members of the Weston A. Price Foundation know, hearty and nutrient-dense sourdough rye bread was a dietary staple for the villagers Dr. Price encountered when he visited Switzerland’s Lötschental in the early 1930s. The Lötschental is located in the upper reaches of the Valais, which is one of Switzerland’s twenty-six cantons (comparable to U.S. states). The Valais contains some of the Alps’ most famous mountain peaks, including the Matterhorn.

Evoking what the Lötschental would have been like in Dr. Price’s day, a modern blogger asks readers to imagine an isolated village surrounded by steep mountains—with “no paved roads, no hospitals, no dentists, no doctors, and no electricity”—subject to “long and cold winters” and reliant on “what [villagers] could harvest and produce for themselves.”9 Despite this bleak-sounding picture, Dr. Price found villagers who were radiantly healthy on a diet of rye bread, raw dairy products and occasional mutton. To this day, visitors describe the valley as a “secret” and “magical” place to experience “unspoiled Swiss rural villages.”10

Rye bread was a natural fit for the Lötschental and other mountain valleys in the European Alps because rye is more robust than other grains,11 with a track record of adapting to extreme climatic conditions, including “the cold of winter, heavy snowfalls, summer heat and drought and high altitudes.”12 Due to its starch profile—quite different from wheat—sourdough rye bread also had the advantage of having a shelf life that could be as long as a few months.11,12 Because villagers baked their bread in communal ovens that they fired up every couple or few months, the bread’s longevity was crucial. Breadmaking required a lot of strength, so it was a task for the village men—and an occasion for wine and beer drinking! The villagers made the bread with a hole near the edge so they could hang it on a hook to cure; they considered two weeks the minimum for well-cured bread.

. . . AND BREAD NOW

The Valais’s written records of rye bread date back to the early 1200s.12 Perhaps due to this history, the Valais is the only region in Switzerland to have a bread with the special “AOP” quality label.13 The AOP designation—awarded not just to the Valais’s rye bread but also to regional cheeses, meats, wines and other products throughout Switzerland—is intended to “help consumers to take a stand against standard and mass-produced products” by guaranteeing that a product is “produced, processed and refined in a clearly defined region.”14 The Valais touts the AOP protection as “help[ing] preserve the landscape by ensuring the continuing cultivation of rye.”15

Notwithstanding the AOP label’s anti-mass-production philosophy, the Valais churns out more than one million loaves of “traditional Valais rye bread” annually.12 Promoters say that the bread “still looks the same today as it did 100 years ago,”12 but would Dr. Price’s Lötschental residents find that it tastes the same?

Probably not. According to the Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity, the AOP rules permit the bread’s producers to add up to 10 percent wheat flour as well as baker’s yeast “for faster and easier preparation.”11 In contrast, the handful of artisan bakers who remain true to rye bread’s “simple ancient recipe” use only pure rye, water and salt—with the all-important sourdough starter (and up to eighteen hours of resting the dough) being the critical factors that imbue the final product with its characteristic sourdough flavor.11

PORTRAIT OF AN ARTISAN BAKER

The substitution of baker’s yeast for the sourdough process began in the nineteenth century, when the “rapid and simple leavening process” facilitated by yeast as well as new methods of mechanized bread production appeared preferable to the lengthy fermentation and time-honored skills required for sourdough bread.16 For some twenty-first century consumers, however, the pendulum has begun to swing in the other direction. For this food-aware subset (whether in the U.S., Switzerland or elsewhere), traditional sourdough bread offers superior flavor, nutritional value and shelf life—without any additives.

Baptiste Dujardin (whose fortuitious last name means “of the garden”) is one of the new generation of bakers in Switzerland participating in the movement to revive artisan food and bread production. Originally from the south of France, Baptiste came to Switzerland following a life-changing stint in his late teens in an intentional community in the United Kingdom. There, he discovered an “alternative” world that spurred an enduring interest in health, traditional foods and the biodynamic (beyond-organic) model of agriculture launched in the 1920s by Austrian philosopher Rudolf Steiner.

After moving to the town of Vevey in the canton of Vaud (the Swiss canton just northwest of the Valais), Baptiste supported himself as a caterer while learning about artisanal food production and breadmaking. He attended local workshops and embarked on extensive experimentation. He also spent three years studying Ayurvedic medicine but later decided that his purpose would be better served by helping build the canton’s budding local and traditional food networks. The canton of Vaud is one of Switzerland’s top agricultural regions, known for its wines and fruits but also leading the country in production of grains suitable for bread-making.17

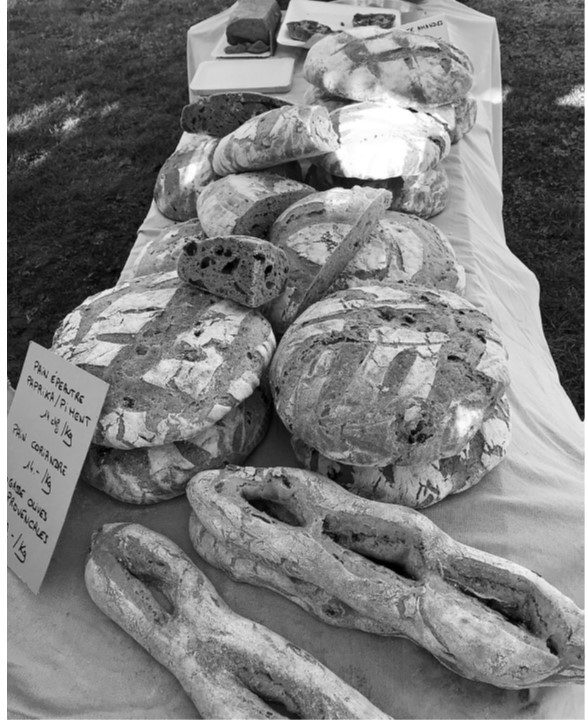

Around 2015, under the rubric of Le Pain Holistique (“Holistic Bread”), Baptiste hung out his shingle as a small-scale producer of artisan breads—all made using traditional sourdough methods. From the beginning, Baptiste has been strict about obtaining grains, seeds and legumes directly from small-scale biodynamic farms that mill the grains on the premises. Benefiting from Switzerland’s geographic compactness, Baptiste only has to drive fifteen minutes to reach the handful of farms with which he partners. Baptiste describes them as permaculture-savvy, “Salatin-style” farmers who integrate livestock, vegetables, grains and fruit trees into their diversified landscapes and, crucially, are willing to innovate and experiment. From these farmers, he is able to obtain rye and several heirloom forms of wheat—spelt, einkorn and emmer—as well as buckwheat and chickpeas. Each of his bread recipes features one of these as the “star ingredient” to highlight the grain’s unique flavor.

In the beginning, Baptiste baked about sixty-five pounds (thirty kilos) of bread per week, but “because people were not used to this type of bread,” he could not always sell all of it. The higher cost of his bread (compared to conventional bakery bread) impeded business growth initially until people began to understand the value of the high-quality biodynamic ingredients and the time-consuming sourdough production process. Over time, Baptiste’s integrity, word of mouth and the breads themselves began to produce many converts. He now has an enthusiastic customer base—who have learned to appreciate the fact that artisan bread is not uniform, and which buys over three hundred and thirty pounds of bread weekly (about one hundred fifty kilos). Baptiste also sells pastured eggs and—true to his Ayurvedic training—a golden ghee “harmoniously prepared” from pastured organic butter. Keeping his overhead low, his primary sales outlet is the local farmers market, which operates twice a week; other outlets include a local health food store (which sells, among other things, kombucha and raw milk), and a foundation that is carrying forward the ideas of Rudolf Steiner.

Baptiste rents space and a 1980s-era bread oven from a commercial bakery, but his long-term goal is to bake in wood-fired ovens—just as the Lötschental residents used to do. Plans are in the works to combine forces with other farmers and food producers to establish a farming community in a small municipality above the town of Vevey. Baptiste envisions the day when all components of the process—grain growing, milling, breadmaking and sales—can unfold in a single location.

REVITALIZING SWISS AGRICULTURE

Baptiste notes that Swiss agriculture is at a crossroads and full of contradictions. On the one hand, businesses like his—partnering with innovative small farmers focused on regenerative agriculture—are at the forefront of efforts to revive Switzerland’s historically prominent role in the organic farming movement. Back in the 1920s, Swiss farmers were among the first to use biodynamic methods; Switzerland continued to refine “organic-biological” farming methods in the 1940s and, in the 1970s and early 1980s, established a Research Institute of Organic Agriculture and the Association of Swiss Organic Agriculture Organisations (Bio Suisse), along with organic growing standards.18,19

At present, small conventional farms in Switzerland are not faring well, in part due to national agricultural subsidy policies that favor “fewer but larger farms.”20 In addition, the technocratic Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has taken sides against small family farms—pushing for “the emergence of larger farms” and advocating “changing current inheritance rules that favour intergenerational farming.”21

Organic farms, however, are booming. Following a decline in the proportion of Swiss farm land dedicated to organic growing in the 2000s, chemical-free agriculture has been trending back upward since 2010.22 At present, one in seven Swiss farms (14.4 percent) is organic, double the proportion in the year 2000.23

The growth in organic farming may be driven in part by increased awareness that Switzerland has a far-reaching pesticide problem. Studies are documenting “scary” and “worse than feared” contamination of waterways in agricultural catchment areas, with seventy to ninety active pesticide ingredients detected per site.24 In 2018, the government even increased the maximum allowable concentration of micropollutants in Swiss lakes and waterways, including establishing a thirty-six hundred times higher limit for glyphosate!25

On farm properties, the pesticide problem is not confined to conventional agriculture. A study publicized in April 2019 reported “frighteningly” high pesticide residues on 93 percent of organic farms sampled in the Swiss midlands—a densely populated area of the country that includes parts of the canton of Vaud.26 (Most of the French-speaking cantons, including the canton of Vaud, embraced the organic farming revivial later than German- and Italian-speaking cantons.22) In 2020, citizens will vote—without the government’s endorsement—on an unprecedented initiative to “ban the use of all synthetic pesticides in Swiss agriculture and the importation of food or animal feed used commercially that is produced using pesticides.”27

Swiss agriculture also presents other paradoxes. For example, notwithstanding its pleasing agrarian landscape and strict regulation of imports,28 Switzerland is far from enjoying food self-sufficiency, with food imports per capita that are among the highest in the world.29 The imports are not just for people; despite the country’s evident strengths in milk and meat production, Switzerland imports extensive amounts of animal feed (especially soy)—an estimated 1.2 million tonnes annually.29,30 Government agriculture researchers report that Switzerland “could be self-sufficient in the case of an emergency,” but only if citizens sacrifice pork, poultry and eggs in favor of “more baked goods and potatoes.”29 (Unfortunately, climate change propaganda and vegan zealotry already appear to be making headway in that direction, with 14 percent of the population reporting a meat-free diet in a 2019 survey, and another 17 percent self-identifying as “flexitarians” who are trying to be “conscious of their meat consumption.”31)

A sizeable segment of the Swiss populace—apparently dissatisfied with the status quo—is tackling agricultural issues at the ballot box. As the “undisputed world champion” of direct democracy, “more than one third of all referendums ever held at the national level worldwide have taken place in Switzerland.”32 And many recent referendums have pertained to agriculture—although with somewhat contradictory results. On the one hand, Swiss voters overwhelmingly endorsed an amendment to the constitution in 2017 intended to “better define the kind of agriculture the Swiss people would like to see more of: local and sustainable.”33 On the other hand, a 2018 food sovereignty initiative designed to address the same types of issues—such as “the decreasing number of farms. . . the pressure of international competition on farmers, [and] the power of large agro-food companies”34—went down to defeat.35

In 2018, over half (56 percent) of all Swiss consumers bought organic products daily or several times a week, and organic sales increased by 13.3 percent over the previous year.36 Although the country’s two large supermarket chains (Coop and Migros) obtained 75 percent of the organic market share between them, direct-to-consumer vendors such as Baptiste and Le Pain Holistique managed to capture 5.2 percent.37 It is hoped that this share will grow as more Swiss people experience the palpable difference that sets artisan food production apart from both conventional and “big organic” farming.

Le Pain Holistique is located in Vevey, Switzerland. For further information, contact Baptiste Dujardin at ateliersholistiques@gmail.com.

SIDEBAR

THE HISTORY OF SOURDOUGH BREAD

Sourdough bread is made through fermentation by lactic acid bacteria and wild yeast—with no added commercial yeast. Tracing sourdough bread’s history, a website (sourdough.co.uk/the-history-of-sourdough-bread/) states: “Wild yeast is used in cultures all over the world in food preparations that are so steeped in culture and history that they have been made long before any form of written words. [. . . ] Until the time of the development of commercial yeasts, all leavened bread was made using naturally occurring yeasts – i.e., all bread was sourdough, with its slower raise [emphasis in original]. Indeed, one of the reasons given for the importance of unleavened bread in the Jewish faith is that at the time of the exodus from Egypt, there wasn’t time to let the dough rise overnight. From Egypt, bread-making also spread north to ancient Greece, where it was a luxury product first produced in the home by women, but later in bakeries; the Greeks had over seventy different types of bread, including both savoury and sweetened loaves, using a number of varieties of grain. The Romans learned the art of bread from the Greeks, making improvements in kneading and baking. The centrality of bread to the Roman diet is shown by Juvenal’s despair that all the population wanted was bread and circuses (panem et circenses).” Noting that sourdough recipes from seventeenth century France called for feeding the starter three times before adding it to the dough, this website comments that “the French were obviously far more interested in good tasting bread over an easy life for the baker.” With the introduction of commercial yeasts in the nineteenth century, however, speed and consistency of production won out over sourdough’s flavor and artisan characteristics.

REFERENCES

- Bread. https://www.eda.admin.ch/aboutswitzerland/en/home/gesellschaft/schweizer-kueche/brot.html.

- The history of sourdough bread. https://www.sourdough.co.uk/the-history-of-sourdough-bread/.

- Is Switzerland the ultimate land of bread? Newly Swissed, June 14, 2012.

- Atchley C. Three bread trends shaping American diets. World-Grain.com, Sept. 21, 2017.

- Tristano D. Growth in upscale doughnut chains becoming a little “strange.” Forbes, Apr. 10, 2018.

- Maison du Blé et du Pain. https://maison-ble-pain.com/wpdev/.

- Swiss Open-Air Museum. https://www.ballenberg.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/images/4_themen/laendliche_wirtschaft/korn_und_brot/FLM_Faltblatt_Korn_Brot_E.pdf.

- Swiss bread recipe: Bütschella—a sweet roll from Graubünden. Cuisine Helvetica, Apr. 11, 2018.

- Are you healthier than a 1930’s primitive Swiss villager? https://behealthynow.wordpress.com/2012/02/29/are-you-healthier-than/.

- Visit to the magic valley of Lötschental. https://www.britishresidents.ch/visit-magic-valley-lotschental/.

- Traditional Valais rye bread. Slow Food Foundation for Biodiversity. https://www.fondazioneslowfood.com/en/slow-food-presidia/traditional-valais-rye-bread/.

- Valais, birthplace of the AOP Valais rye bread. https://www.valais.ch/en/about-valais/local-products/rye-bread.

- Valais rye bread AOP: the real thing. https://www.myswitzerland.com/en-ch/experiences/food-wine/valais-rye-bread-aop-the-real-thing/.

- AOP and IGP: quality labels with character. https://www.cheesesfromswitzerland.com/en/production/aop-and-igp.

- Rye bread from the Swiss Valais: pain de seigle valaisan or walliser roggenbrot. http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/51444/rye-bread-swiss-valais-pain-de-seigle-valaisan-or-walliser-roggenbrot.

- Sourdough bread. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/food-science/sourdough-bread.

- https://www.agirinfo.com/fileadmin/agir/Agriculture/Documentation/En_terre/L_agriculture_en_terre_vaudoise_2016.pdf.

- Bio Suisse’s roots. https://www.bio-suisse.ch/en/ biosuissesroots.php.

- FiBL Switzerland—40 years of organic farming research. https://www.fibl.org/en/switzerland/location-ch.html.

- Three Swiss farms close a day. SWI swissinfo.ch, May 11, 2017.

- The unseen environmental cost of Swiss farming. Le News, Mar. 2, 2015.

- Swiss organic farming continues to grow but with big cantonal differences. Le News, Sept. 5, 2018.

- Bio Suisse. Organic sector in numbers 2018, Figure 1. https://www.bio-suisse.ch/media/Ueberuns/Medien/BioInZahlen/JMK2019/EN/2018_organic-sector-in-numbers_en.pdf.

- Excessive levels of pesticides found in small streams. SWI swissinfo.ch, Apr. 2, 2019.

- Swiss government raises allowable limits for pesticide residues in waterways. Le News, Mar. 27, 2018.

- Pesticide residues found on 93% of organic Swiss farms. SWI swissinfo.ch, Apr. 7, 2019.

- Government rejects vote to ban synthetic pesticides in Switzerland. Le News, June 26, 2019.

- Bio Suisse. Organic sector in numbers 2018, Figure 7. https://www.bio-suisse.ch/media/Ueberuns/Medien/BioInZahlen/JMK2019/EN/2018_organic-sector-in-numbers_en.pdf.

- Bondolfi S. Does Switzerland produce half of all the food it needs? SWI swissinfo.ch, Sept. 11, 2018.

- Swiss to vote on banning factory farming. SWI swissinfo.ch, Sept. 17, 2019.

- 2.6 million Swiss are reducing their meat consumption. https://www.livekindly.co/2-6-million-swiss-reducing-meat-consumption/.

- Kaufmann B. The way to modern direct democracy in Switzerland. https://houseofswitzerland.org/swissstories/history/way-modern-direct-democracy-switzerland.

- Chandrasekhar A. Swiss voters demonstrate appetite for food security. SWI swissinfo.ch, Sept. 24, 2017.

- Tognina A. Radical change for Swiss agricultural policy goes to vote. SWI swissinfo.ch, Aug. 16, 2018.

- Swiss reject agriculture schemes in national vote. The Local, Sept. 23, 2018.

- Bio Suisse. Organic sector in numbers 2018, Figures 8 and 10. https://www.bio-suisse.ch/media/Ueberuns/Medien/BioInZahlen/JMK2019/EN/2018_organic-sector-in-numbers_en.pdf.

- Bio Suisse. Organic sector in numbers 2018, Figure 9. https://www.bio-suisse.ch/media/Ueberuns/Medien/BioInZahlen/JMK2019/EN/2018_organic-sector-in-numbers_en.pdf.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly journal of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Winter 2019

🖨️ Print post

Leave a Reply