🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

Biofuels Effect on World Wide Elevated Food Prices

On December 18, 2010, a twenty-six-year-old street produce vendor in Ben Arous, Tunisia named Mohamed Bouazizi, set himself on fire in the public square as an act of protest and terminal frustration over his personal situation. The straw that broke his back was an ordinary shakedown by Tunisian police for two hundred dollars and his lack of an administrative permit. Bouazizi’s act of protest served as the ignition spark felt across the Mediterranean that led to what is generally known as the Arab Spring.

Popular uprisings and protests across the region resulted in three civil wars and an ousting of entrenched rulers from the western Sahara to Iran. The commonly ascribed root causes of the Arab Spring are autocratic and punitive rulers, lack of populist democratic norms, endemic state corruption, a ballooning population of young citizens and permanent unemployment or low prospects for social and financial fulfillment. Underneath these visible social factors, however, another less publicized factor played a key role in lighting the fuse: rapidly escalating prices for staple foods.

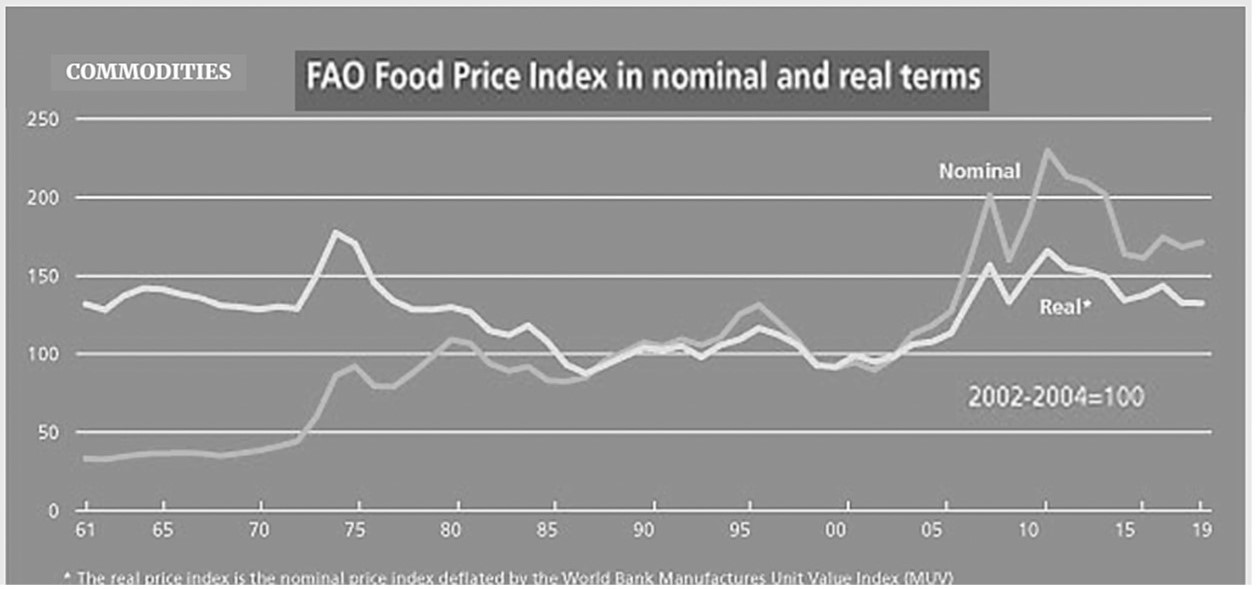

Despite the developed world being stuck in a global recession and the general collapse in commodity prices that occurred as fallout of the subprime-mortgage-induced financial collapse of 2008, by 2010, global food prices—as measured by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO’s) Food Price Index (FPI)—had recovered and exceeded core food price levels during the commodities super cycle that occurred between 2000 and 2008 (Figure 1).

If the rest of the global economy was in a period of economic stagnation, why had international food prices become so elevated? The headline answer assigned at the time was climate change or weather-related food supply disruptions. These disruptions had occurred in Russia (forest fires), Australia (floods), Argentina (drought) and the Middle East (yellow dust/depleted aquifers) across 2010—an early example of “climate change” being blamed as the underlying cause of. . . everything.

Biofuels & the Global Food Supply

The less publicized and larger reason was that the global food supply-and-demand balance had fundamentally changed between 2005 and 2010. Massive biofuels programs enacted by the main OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) nations incentivized the blending of ethanol into gasoline/petrol and biodiesel into petroleum diesel. Ethanol is primarily produced from the fermentation of staple carbohydrate crops such as corn, sugar cane, wheat, barley and cassava/tapioca, while biodiesel is primarily produced through the esterification or trans-esterification of vegetable oil from soybeans, palm, rapeseed/ canola, sunflowers and used or virgin cooking and frying oil.

Implementation of these programs began during the mid-2000s due to a complicated amalgam of reasons including rising crude oil and energy prices, questionable environmental and greenhouse gas (GHG) benefits, and farm region votes and financial subsidies.

Since 2000, the global supply of biofuels, produced for internal combustion engine usage, had grown from less than 200,000 bpd (barrels per day) to 1.7 million bpd, a roughly eightfold increase. (Note: This is on an Oil Equivalent Basis; the physical volumetric biofuel production is closer to 2.5 million bpd, but ethanol has only 70 percent the volumetric energy density of petroleum gasoline, requiring a conversion to compare on an equivalent basis.) Biofuels today comprise around 1.5 to 2 percent of the supply of refined products delivered globally. Production is concentrated in the U.S., Argentina and Brazil, Indonesia and Malaysia, and the European Union. The U.S. alone accounts for about 55 percent of global biofuel supply and demand, where 10 percent of just about every gallon of gasoline sold in the U.S. is ethanol (see Figure 2).

On a macroeconomic level, the corresponding impact on the food and energy markets is orders of magnitude apart: small for the energy markets at 1-2 percent of global refined product supply and quite large for the food side of the equation at greater than 10 percent of total potential food supply. Biofuels programs upset the global food balance, inflaming regions that have the highest food import burden—namely, the countries of the Middle East, North Africa, sub-Saharan Africa and Northeast Asia (see map, next page).

To put things in context, global production of corn stands at approximately 1.1 billion metric tonnes, of which the U.S. produces a third (three hundred fifty million metric tonnes); a full third of the U.S. corn grown is designated for fuel ethanol and by-product production. What this means is that 10 percent of the global corn supply ends up being converted for fuel in U.S. gas tanks. In caloric or food supply terms, this number is even more alarming. Corn converted into fuel ethanol contains enough calories to feed 5 percent of the global population each year, or the entire population of the U.S. (three hundred fifty million people).

The UN currently estimates that seven hundred million people globally live in food scarcity or are chronically hungry. Let that sink in: slightly under 10 percent of the world’s population is undernourished and calorie-deficient, even though world food production is enough to provide all of them with twenty-five hundred calories a day. Yet the global biofuels industry and politicians have successfully enacted legislation and policies that convert that equivalent volume of calories into fuel for internal combustion engines. Legislation that transforms edible food into a gasoline substitute when food scarcity is still prevalent is grossly immoral.

Empty Claims

Biofuel advocates pushed most of the large-scale biofuel programs on the basis of three hypothesized benefits: increased energy independence (read this as reduced foreign imports of energy); reduced greenhouse gas emissions (burning biofuels instead of petroleum fuels); and the murky and ill-defined benefit of farm crop price support. Of these three purported benefits, only the last one has proven to have any legitimacy.

Since 2005, U.S. energy security or independence has increased substantially in that U.S. production of crude oil has grown from roughly 5 million bpd to 12 million bpd, with a subsequent drop in crude oil imports of 4-5 million bpd. However, the growth in domestic production has nothing to do with biofuels and everything to do with the application of new technology in the form of hydraulic fracturing in the oil patch.

If anything, a better argument can be made that biofuels programs increase energy insecurity. In the U.S., the biofuels program reduced petroleum gasoline demand by 10 percent, affecting the refining balance in the U.S., where refineries are designed to disproportionately produce gasoline. Since 2008, eight refineries have closed down on the East Coast, leaving the region more dependent on gasoline imports and gasoline pipeline deliveries from the Gulf Coast. Both are prone to single-point supply disruptions.

The reported environmental benefits of biofuels were either oversold or outright fictitious. The central espoused environmental benefit of biofuels is the self-contained carbon dioxide cycle inherent in all plants, in which the crops absorb carbon dioxide through photosynthesis during the growing phase, only to rerelease the same amount of carbon dioxide through thermal combustion. It is true that on average a gallon of ethanol has a lower GHG emissions footprint than a gallon of petroleum gasoline (on a well-to-wheel basis which incorporates the GHG emissions with production, transportation, transformation and combustion) by about 20 percent.

This 20 percent GHG reduction holds true only when existing cropland (as of 2008) is used to grow the biofuel raw materials. If natural lands (such as prairies, forests, bogs, and other fallow areas) are converted into cropland to grow the biofuels, this “land-use change” in most cases releases more carbon dioxide into the atmosphere than is removed through the combustion of biofuels versus fossil fuels. This Titanic-sized loophole has the effect of making biofuels legislation net-negative GHG on paper, but often net-positive in real world application. This is the big “if” behind the biofuels story and is even codified in the U.S. biofuels regulation.

Since 2005, almost ten million hectares of arboreal peat tropical rainforest in Indonesia and Malaysia have been cleared and converted into palm oil plantations, releasing an enormous amount of carbon in the process. The expected destination for most of this palm oil is—and was—conversion into biodiesel and export for consumption in Europe and the U.S. Ranges vary widely, but it is estimated that since 2015, land use change in those two countries is responsible for 2.5 percent of carbon emissions globally. This is more than the state of California or the entire global commercial aviation industry. Similar clearing has occurred in Brazil, Argentina and the U.S.

One of the underlying premises of the U.S. biofuels program was an inherent expectation of GHG reductions through no change in existing land usage. This was to be reviewed and studied by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Congress every two years. However, since the passing of the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard in 2008, no subsequent study has been commissioned. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA’s) online published data show that acreage planted for corn and soybeans has increased by 10 percent over that time.

Fueling Industrial Crops

Biofuels programs create artificial demand for the world’s major factory-farmed industrial crops. These types of crops are grown and developed mostly by corporate farm conglomerates or big corporations. These entities have been the ultimate beneficiaries of the U.S. and global biofuels programs, largely to the detriment of food supply, energy security and the environment. These programs should be called out for what they are—Big Ag corporate welfare, at the expense of everything else.

The main U.S. biofuels legislation is set to expire and/or come up for debate and renewal in 2022. Given the high costs to the global food supply and minimal-to-negative benefits on energy security and the environment, my position is that it should not be renewed. Given the role of entrenched corporate and political interests in our legislative process, I suspect that this Frankenstein monster will be revived if not supercharged with more convoluted legislation—legislation that primarily serves the interest of Big Ag.

For you as an individual reader, a logical approach to forming your own opinion regarding the U.S. Biofuels Program is to make a personal list of winners and losers (or for-and-against camps) if the U.S. biofuels legislation were to be extended and renewed in its current form. My personal list would look something like the following:

Winners: corporate agriculture, farm state politicians, lawyers, consultants, lobbyists, traders and other supply chain intermediaries.

Losers: oil companies, beef producers, grocery retailers, environmentalists, malnourished populations worldwide, food importing regions, global ecosystem, food price inflation, and U.S. citizens.

SIDEBARS

More Concerns About Biofuels

Another concern about the use of biofuels centers on air pollution. As detailed in her article “Air Pollution, Biodiesel, Glyphosate and Covid-19” (Summer, 2020), Stephanie Seneff notes that one reason for the significant differences in Covid-19 susceptibility around the world may be the underlying toxicity burden of the population in each region. For example, studies have found a striking correlation between exposure to particulate air pollution and the likelihood of dying from Covid-19.

All of the Covid-19 hot spots share a common thread of a high rate of adoption of fuels derived from biomass, nearly all of which can be predicted to be heavily contaminated with glyphosate. Glyphosate could be released along various stages of biodiesel fuel production and use.

Animal studies comparing biodiesel fuel with standard diesel for their potential toxic effects indicate that biodiesel may be significantly more toxic.

Glycerin is a major waste product of biodiesel production, and both glycerin and its byproduct propylene glycol are e-cigarette additives. Symptoms seen in vaping illness match closely with symptoms of Covid-19.

Multiple mechanisms of glyphosate toxicity can plausibly explain the acute reaction to Covid-19 seen in patients who end up in the ICU. Inhaled glyphosate may substitute for glycine in important lung surfactants, compromising lung function. It is plausible that the rapid rollout of 5G may work synergistically with glyphosate to enhance effects seen in those with Covid-19.

Edison Versus Tesla

In my last article, “The Electrification Revolution” (Fall, 2021), I erred in stating that “Edison’s alternating current system would become the chosen form for producting energy.” Actually, it was Tesla who advocated the alternating current (AC) system, which eventually prevailed over Edison’s direct current (DC) system.

The fathers of the electric revolution were three men of great modern renown, and bitter rivals, Thomas Alva Edison, George Westinghouse (the businessman) and his scientific partner Nikola Tesla. All three men contributed greatly to scientific progress and invention, but in the end the AC system of Westinghouse-Tesla would become the chosen form for producing mass electricity due to its inherent advantage, namely power transmission over long distances with lower transmission losses. This system persevered despite an aggressive propaganda campaign by Edison to demonize the safety of AC through the public electrocution of circus animals and convicted murderers.

After Edison solved the puzzle of the incandescent filament light bulb, he turned his attention to spreading the gospel of electricity and direct current. On January 12, 1882, Edison’s Electric Light Company began operation of the world’s first power plant in London. The coal fired power plant was known as Holburn-Viaduct Power Station. When operating, the Power Plant produced about 95 kW of electrical power (125 HP) and had the capacity to illuminate over seven thousand lamps across London. This first power plant produced Edison’s direct current electricity and the plant operated for only four years before closing, following significant financial losses. Edison’s second adventure into power generation started operation the same year (September, 1882) at the Pearl Street Station in New York City and had a similar troubled operating history.

The first major Westinghouse-Tesla foray in electrical power generation occurred in upstate New York at Niagara Falls, where a 5,000 HP alternating current hydroelectric power station was constructed between 1893 and 1896. The first operation transmitted electrical power to the City of Buffalo about thirty kilometers away. The harnessing of the Niagara River continues to this day with capacity of the rebuilt (several times) and modernized hydroelectric plant currently standing at 2,500 MW (3.4 million HP). This success, coupled with the positive publicity of the Westinghouse-Tesla exhibit at the 1893 World Fair in Chicago, ended the “War of the Currents” in favor of the Westinghouse-Tesla alternating current system and provided a new blueprint for humanity to harness the power of combustion and electrification.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly journal of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Winter 2021

🖨️ Print post

Leave a Reply