🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

In 146 BCE, the Roman General Scipio Africanus Aemilianus completed the third and decisive Punic War, which had consumed the Western Mediterranean for almost one hundred years. The prize: control of trade in the western Mediterranean and de facto dominion over Western Europe. Spain, Portugal, England and France would subsequently capitulate to Roman expansionism over the next one hundred fifty years.

There remained a problem though. . . Carthage. What to do with the people of Hannibal and the city of Carthage? The North African city-state had been the dominant regional power for over a century, principal rival to Rome itself, and had come within an elephant’s tail of conquering the Roman capital city during the Second Punic War, fifty years prior. Now the capital city of Carthage lay smashed and burned to the foundation stones. Through experience, the Roman leaders knew that if they let Carthage survive, in due time she would rise again as a permanent thorn in the paw of mighty Rome.

As the Roman generals ruminated, a policy solution emerged to deal with the “Carthaginian problem”—an environmental policy solution. The Romans were fond of good policy solutions, which enabled them to control Europe and the Mediterranean for the better part of eight hundred years. What if they took away Carthage’s ability to grow their own food and support a sizeable and robust population of fighting-age men? What if they made Carthage dependent on Rome for basic sustenance, a true vassal state?

The salting of fields to cripple a civilization was not a new concept and had been employed throughout antiquity. A favored military practice of the Assyrians and Hittites, it was such a popular “remedy” that it received mention in the two great surviving books of the age, the Old Testament of the Hebrew people and Homer’s Odyssey. Being steeped in history themselves, the old patriarchs of Rome agreed on the solution and thus the wheat fields of Carthage were plowed with salt and rendered economically useless.

Funny thing about targeted environmental policies—they are often quite effective at achieving their stated policy goals. We don’t hear or read much about Carthage after the Punic Wars; the once-great commercial empire, which brought the Phoenician alphabet to the Western world, was now humbled and ultimately forgotten in the desert sands.

ENVIRONMENTAL TRIBALISM

Since humans began to organize themselves into multi-family societies some twenty thousand years ago, environmental decisions have been at the center of civilization. In very simplified terms, environmental policy can be reduced to a society’s decision on how to use the Earth’s resources in a way that provides the most benefits and incurs the least amount of cost to that society. This form of societal planning encompasses everything from “Should we use this creek to irrigate our fields?” to assessing the environmental health of the Earth and whether the roughly eight billion human inhabitants are a net benefit or negative to the long-term health of the only planet we’ve got. . . for the time being.

On paper, this seems like a fairly straightforward concept: The Earth is endowed with a fixed amount of resources and we (humans) should make conscientious choices to use those resources to improve the human condition and preserve those resources for current and future generations. Unfortunately, this basic concept of human self-interest has a rub—there is always a rub. The challenge of forming and enacting environmental policy is that the “resources,” the “best use” and, most importantly, the “cost” of utilizing those resources are all subjective concepts. Ask any two individuals—much less two politically appointed decision-makers—and you are likely to get wildly different definitions and interpretations of those key concepts.

Most of us have internal definitions of what kind of policies, laws and plans constitute “good” and “bad” environmental management. However, broad consensus is elusive if not unfeasible, and environmental tribalism has become the standard when discussing how best to use the planet’s resource endowment. The spectrum of environmental viewpoints runs the gamut from the rapacious free enterprise philosophy (“any regulation is bad regulation”) to the nature’s guardians philosophy (“any disturbance is a bad disturbance”), and every position in between. The broad and far-reaching concept of “the environment” and the management of that environment has become the modern-day equivalent of the Gordian Knot.

With the above disclaimer in mind, the remainder of this article will provide a general overview of how environmental regulation in the U.S. is organized and examples of the good, the bad and the ugly of enacted environmental regulation.

ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY AND REGULATION, U.S.-STYLE

In the United States, environmental policy and regulation are controlled by the U.S. government, which receives a broad and diverse swath of input from industry, non-profit organizations and wealthy individuals with pet causes. The principal edifice through which U.S. environmental policy is conceived, enacted and enforced is the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in cooperation with local state-controlled entities such as CARB (California Air Resources Board), the TCEQ (Texas Commission on Environmental Quality) and the NJDEP (New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection). Similar to law enforcement regulations, this patchwork system of local, state and federal environmental departments creates a complicated spaghetti bowl of different laws that occasionally align, but more often conflict with each other.

Although the U.S. environmental regulation apparatus has many unique features, the basic structure of environmental policy aligns along the following core functions or enforcement departments. It should be noted that the general organization and concept is similar around the world once adjusted for local acronyms and customs.

- CLEAN AIR: Focuses on reducing criteria pollutants from the air, including ozone, nitrous oxides (NOx), sulfur oxides (SOx), carbon monoxide (CO), particulate matter (PM) emissions, heavy metals (lead, mercury), fugitive emissions (methane-focused, although broader in actuality) and, in some locales, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (primarily carbon dioxide). A good way to think about the major focus of clean air regulation is as the regulation and control of combustion and combustion’s by-products.

- CLEAN WATER: Focuses on managing pollution of rivers, streams and lakes; providing potable drinking water; and monitoring and managing the water intake and discharge from industrial operations that use public water resources.

- CLEAN LAND: Focuses on cradle-to-grave management of hazardous substances, land management, fertilizer and herbicide usage, and waste disposal sites. In the U.S., there is no explicit Clean Land Act, due to the unique U.S. structure of property ownership, mineral rights and federal land control coming under the U.S. Department of the Interior. The salting of Carthage’s fields would have fallen under this department.

- HAZARDOUS MATERIALS AND RECYCLING: Sometimes organized as a subdivision of the “clean land department,” such regulations focus on monitoring and regulating hazardous materials frequently used in building applications such as lead, asbestos, polychlorinated bisphenols, aerosols, refrigerants and radon, along with state and national recycling and waste management practices.

- NUCLEAR: Focuses on all matters involving the management of nuclear fuels, covering extraction, refinement, weapons usage, civilian electricity generation usage and temporary and permanent disposal. Also, nuclear regulations typically serve as the focal point for response to an uncontained nuclear accident. When formed in the 1940s, this was managed by the Atomic Energy Commission. This branch of government was folded into the Department of Energy during the 1970s. Due to the specific hazards associated with nuclear fuel usage and radiation, in most parts of the world this aspect of environmental regulation is handled by a separate dedicated agency.

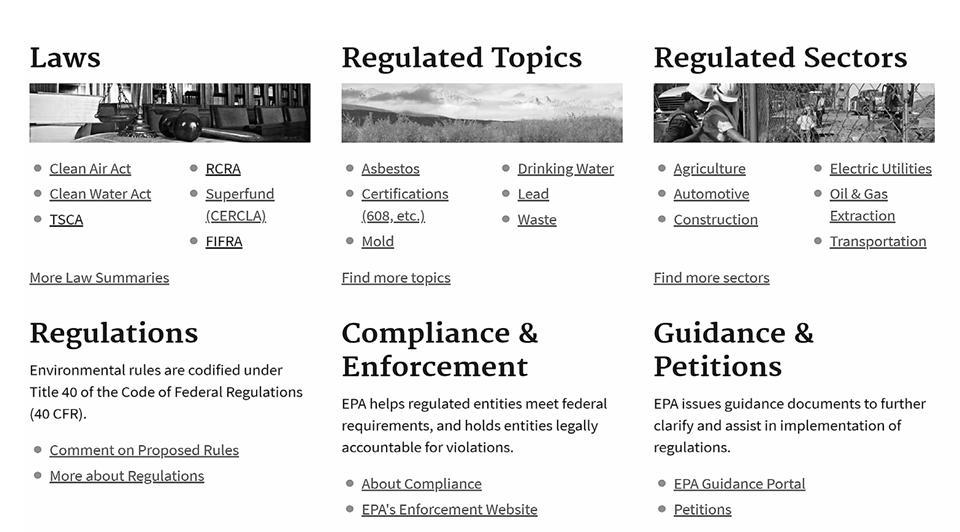

Although U.S. laws are not quite consistent with the broad organizational system for environmental regulation just described, they largely conform to this structure (see screenshot of the U.S. EPA home page).

GENESIS OF U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL LEGISLATION

The foundations of the modern U.S. environmental regulatory system began to take shape in the late 1950s and early 1960s, and with very good reason. Since the 1870s, the U.S. had experienced an extended period of growth and development that transformed the nation from its former colony status into the workshop of the world—a designation now enjoyed by China.

After seventy-five years of unrestrained extractive activities, the U.S. was overdue for a period of regulatory pushback and environmental reform. The response to America’s ultra-aggressive form of private industry started at the close of the nineteenth century with the passage of the Sherman Antitrust Act (1890) and the break-up of the big industrial monopolies, and continued through to the passage of the 1970 National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and the creation of the Council on Environmental Quality (the predecessor organization of the EPA). These steps set the stage for the passage of three landmark environmental regulatory acts during the early 1960s and 1970s: the Clean Air Act (1963), the Clean Water Act (1972) and the Endangered Species Act (1973). All subsequent U.S. environmental regulation has flowed from the foundational principles established by these three laws.

The other key contribution to the modern environmental movement was an emerging national environmental consciousness that started during the late 1950s and continued into the early 1960s. This was best exemplified by Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, published in 1962, which focused on pesticide usage in the U.S. and the active disinformation campaign on the part of big agriculture and petrochemical interests to obscure the not-so-hidden side effects of intensive crop spraying.

In addition to serving as the genesis event for most modern U.S. environmental legislation, the passage of these three foundational laws led to the large-scale clean-up and remediation of America’s natural habitat from coast to coast. Although these laws have without a doubt increased the cost of doing business in the U.S., they also have by and large been successful in their overarching objective to scrub clean America’s heavy industrial past.

National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS) is a measure of the “cleanliness” of U.S. air. Using this as a benchmark, since its initial adoption in 1963 the Clean Air Act, though sometimes maligned, has been an overwhelming success. The chart on page 54 shows the significant reduction in per capita criteria air pollutant and carbon dioxide emissions over the past fifty years, without a significant penalty on economic growth or energy availability.

GASOLINE: THE GOOD

Nothing that we use in daily life has received more of a transformation than U.S. gasoline. Although they are still both technically “gasoline,” the 1970s version looked almost nothing like its modern-day equivalent. About 80 to 85 percent of U.S. internal combustion-based vehicles are designed to run on gasoline.

As it is a material source of U.S. air emissions and pollutants, the reformulation of gasoline has been front and center in most U.S. environmental legislation (see Chronology, page 57). For example, gone from gasoline are the lead (tetra-ethyl lead), the heavy aromatics (think kids sniffing gasoline to get stoned) and the sulfur (reduced by 98 to 99 percent); in addition, catalytic converters minimize the formation of nitrous oxides and carbon monoxide emissions by promoting full combustion. Since precious metal catalysts in the converter are poisoned by sulfur dioxides, the removal of sulfur from gasoline now ensures proper conversion efficiency of the converter and has the knock-on benefit of reducing acid rain from sulfur dioxide emissions. Reformulation of the gasoline recipe has also involved many other changes, such as limiting the amount of high volatility butane blended into gasoline, adding an oxygenate (such as MTBE or ethanol) and much tighter control of gasoline’s boiling range.

The transformation of gasoline started in California in the 1960s and is now in place nationwide. The best tactile example of the improvement in U.S. gasoline and the push to make it cleaner is the reduction in direct visible smog in the Los Angeles basin. Those clear California skies, now available on a daily basis (wildfire dependent), are a far cry from the smog-choked images of Los Angeles streets from the 1960s (see below).

GASOLINE: THE BAD AND THE UGLY

However, while the changes to U.S. gasoline highlight “the good” aspects of U.S. environmental policy, they also highlight “the bad” and “the ugly.” As with many things—and as a key takeaway from this piece—the success of the U.S. environmental regulations in the 1970s and 1980s paved the way for new and more tangled regulations in the 1990s and 2000s. This second- and third-generation environmental legislation reflects a jump in technical complexity—and a newfound interest in environmental legislation by complex, diverse and often diametrically opposed business and political interests.

Two laws passed in the 2000s under George W. Bush illustrate the bad and the ugly side of environmental legislation. First was the Energy Policy Act of 2005, a piece of legislation quickly followed by its cousin, the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act, which, among other things, created the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS). (See sidebar, page 56 for a sample of the complex language from the current Renewable Fuel Standard.)

The stated overarching policy goals of both pieces of legislation go something like this (author’s paraphrase and license):

- Improve U.S. international relations by reducing dependence on imported crude oil.

- Reduce U.S. greenhouse gas emissions from automobiles by 10 to 20 percent.

- Increase the blending of biologically derived fuel into the U.S. gasoline and diesel blend pools by 10 to 20 percent.

• Increase U.S. usage of corn-derived ethanol and biomass-based diesel. - Create a market-based trading mechanism to incentivize increased levels of biofuels blending in the U.S. transportation fuel pool.

- Provide technological funding and incentives for the production and mass adoption of second- and third-generation biofuels not based on edible foods (think switch grass and prairie grass).

- Minimize U.S. land use changes.

With so many naturally aligned policy objectives, what could go wrong? A lot, as it turned out, particularly in the hands of the modern U.S. pay-to-play political system. After thousands of pages of technical regulation, here are a handful of observations on what the U.S. Renewable Fuel Standard looks like when applied in practice:

- A massive and permanent subsidy program for U.S. big agriculture interests, namely, corn and soybean growers and the seed and herbicide conglomerates.

- A lobbyist and special-interest regulatory orgy.

- Permanent employment program for the U.S. legal profession.

- No measurable change to U.S. greenhouse gas emissions specific to this legislation.

- A reduction in U.S. crude oil imports completely unrelated to this legislation. U.S. oil imports have been reduced because of technological breakthroughs in U.S. domestic crude oil production (a little thing called hydraulic fracking).

- A financial instrument—U.S. renewable fuel credits—with almost no regulatory oversight that ranks as one of the most volatile and gameable financial markers in the past ten years.

- The conversion of a huge amount of consumable food calories into U.S. gasoline, something on the order of 10 percent of the global food supply.

- A weird if almost unbelievable set of political alliances, namely, one that puts U.S. refiners on the same side of the negotiating table as environmentalists and pits big grain against big meat against food wholesalers (grocery stores) against automotive manufacturers. The list of unnatural bedfellows goes on and on.

- No follow-up study or technical analysis on the impact of land use changes as a result of this bill.

- No real or tangible progress in the development of non-food-based biofuels in the U.S. or the world as a whole.

The RFS legislation has been an annually contested piece of legislation that has spawned hundreds of lawsuits and almost continuous debate in the legislative branch. The current regulations are set to expire in 2022; the subject is considered politically toxic and one that nobody in the U.S. Congress wants to work on. One thing is certain, however: whatever happens with the 2022 renewal or sunsetting of this program, the U.S. government will be firmly in a position to pick the winners and losers through regulatory arbitrage—exactly as the Founders envisioned our modified democratic-republic system working.

SPECIAL INTERESTS PREVAIL

It should be self-evident that good environmental policy is a cornerstone of productive civilization growth and an important mechanism in guiding the success or failure of any society. And as shown in the Carthaginian and Roman example, a targeted environmental policy can be used to extinguish a once-thriving culture.

In the U.S. specifically, the major environmental legislative initiatives of the 1960s and 1970s were necessary and successful in cleaning up widespread air and water pollution that existed after one hundred years of unrestrained extractive activities. However, since those broad-reaching and measurable early successes, environmental legislation has become a catch-all umbrella for moneyed interests and pet projects in our current corrupt political system. What was once the shepherd, helping us navigate the complexities of our modern industrial world, has revealed itself today to be nothing more than a special-interest wolf camouflaged as environmental goddess.

It is also becoming increasingly clear that the abject failure of the late 2000s Renewable Fuel Standards is the harbinger of worse to come and not an outlier. We should all expect a continuation of the bad side of the environmental coin when it comes to the troubling legislative storm clouds forming on the horizon—a massive vampire squid of environmental legislation addressing the perceived existential crisis of climate change.

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly journal of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Spring 2021

🖨️ Print post

I would like information on radon