🖨️ Print post

🖨️ Print post

Covid has left an indelible mark on life in the third decade of the twenty-first century. If you did not experience Covid symptoms yourself, you certainly know someone who did and you may even know someone who died.

Among those hospitalized with Covid are folks who are experiencing serious aftereffects that affect all organ systems—what has been labeled “long Covid.” Dr. Ziyad Al-Aliy, director of the Clinical Epidemiology Center and research head at the Veterans Affairs St. Louis Health Care System, describes the breadth of organ system dysfunction in “long Covid” as “absolutely jarring.”1

PULMONARY FIBROSIS

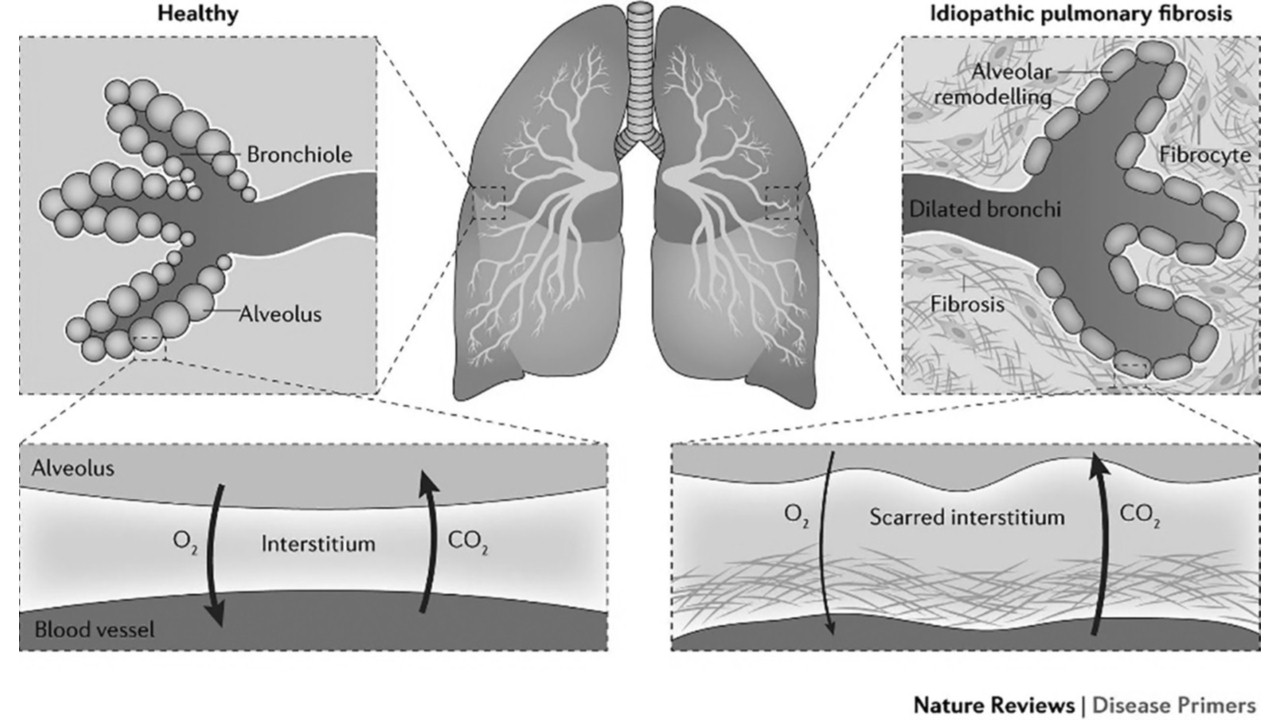

Where the lungs are concerned, “idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis” is the term doctors use to describe the Covid-related lung condition involving abnormal thickening and scarring of connective tissue (fibrosis). The eventual loss of lung elasticity can cause persistent cough, chest pain, difficulty breathing and fatigue.2 Whereas “idiopathic” means “of unknown origin,” there are many well-known causes of pulmonary fibrosis, including long-term occupational encounters with inhaled asbestos fibers (for example, in twentieth-century shipbuilding and maintenance); exposure to dust from substances such as coal (mining), silica (highway repair), hay and bird and animal droppings (farming); and air pollution.

The development of fibrous connective tissue can be a normal bodily response designed to repair injury or damage, but under some circumstances, the process goes awry.2 What is not known is why, in the case of pulmonary fibrosis, alveolar tissue healing veers in a pathological direction. Dr. Jaymin J. Kathiriya and colleagues offer an explanation in a study published in January 2022 in Nature Cell Biology.3 The lungs contain different kinds of epithelial (lining) cells, which all have specific functions. In the lung-healing process, this differentiation can become confused, resulting in cells proliferating where they do not belong and preventing normal function. More specifically, what these researchers report is that cells lining the bronchi (the air-passage tubes) replace the alveoli—the one-cell-thick tissue through which oxygen and carbon dioxide need to travel, into and out of the blood, respectively. Two different functions; two different structures. Thus, pulmonary fibrosis—which compromises the lungs’ ability to defuse oxygen and carbon dioxide.

RETHINKING HEALING

The medical community has taught the public to expect quick fixes—with drugs, and now vaccines. In the case of long-haul Covid lung injuries, however, there is no quick fix. For a century, in fact, mainstream medicine has been unable to prevent or reverse the long-lasting effects of pulmonary fibrosis, nor did it have any solution to offer for the prevention or reversal of the fibrotic changes observed twenty years ago with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS). Physicians such as Dr. Al-Aliy are now arguing for the need “to take long Covid more seriously and devote resources to it” so as to discover new treatments.1

When you are depressed and anxious about your health, it’s hard to start rethinking the meaning of healing and learn new approaches to well-being. Itself a novel idea, “well-being” is a state of body, mind and spirit harmony that can foster the joy of inner peace. Even when your body is not as fully functional as your brain desires, you can employ positive energy to make the best of your situation.

I make no claims about curing Covid-damaged lungs—that is, returning them to their pre-Covid state. Rather, it is my thesis that the body has many untapped back-up and interconnected support systems—ready and waiting for recognition—which can help you eliminate inefficiencies and restore hope for a more functional future. This approach is powerful no matter what ails you because it grounds you in your body, rather than in your brain. As you begin to listen to your body’s messages, you can take appropriate positive action.

Let’s face it: healing can be arduous work— whether physically, mentally, emotionally or spiritually. I believe that a healing strategy that involves appreciation for the body, efficient breathing, ample movement, appropriate hydration and excellent nutrition—applied with focus and commitment—can bear fruit.

APPRECIATE YOUR BODY

To establish a solid commitment to healing, start with an appreciation of your body. Love your body unconditionally, as you would a two-year-old. It is yours to nourish and nurture.

Recognize the fact that your body deserves total respect for its responsiveness—positive and negative—and its resilience. The brain, which sits on top of the body as though it is in total charge, would like to convince you otherwise, but actually, the body’s true brain, called the enteric nervous system, is in the gut. So, when you have “a gut feeling,” it is your sensible gut speaking—and you must listen.

The skirmish between brain and body intelligence often takes place in the neck. If you have trouble swallowing or speaking, or if your neck is stiff, that’s your body screaming at you. Listen and figure out the message.

You will realize you love your body when you can stand naked in front of a mirror and acknowledge your admiration for your beautiful body. Have fun with it! Remember that while you are not actually your body, your body is the home of your soul and spirit and allows you to be on earth and recognizable as an individual. So, go ahead and admire your body. This can provide motivation for daily self-care.

BREATHE EFFICIENTLY

Once you are committed to self-care and healing, learn how to breathe efficiently, focusing on your outbreath. Restoring health and well-being requires energy, and breathing is the source. Since breathing has an impact on every organ system, muscle and cell in your body, it serves as a springboard to launch a healing journey. When you have understood, learned and used the focus on the outbreath, other layers of healing and well-being will emerge.

There are three reasons why breathing affects the whole body. Let’s start with the vagus nerve—the tenth cranial nerve—which is the longest and most complex of the twelve cranial nerves leading from the brain stem to the far reaches of the body. The vagus nerve wanders from the brain stem all the way to the colon, along the way connecting with the middle ear, vocal cords, heart, lungs and intestines. In addition, the vagus nerve interacts with the autonomic nervous system, which regulates involuntary physiological processes like breathing, heart rate, blood pressure and emotional states. Your outbreath has a positive influence on this nerve and all the organs it enervates.

The diaphragm is the second reason breathing affects total well-being. Though it is the most important muscle of respiration, the diaphragm is not under your conscious control, but you can affect it by alternately squeezing (outbreath) and releasing (inbreath) your belly muscles. In 2018, Italian researchers shed new light on the broad array of diaphragmatic functions, illustrating why the diaphragm is not only “the motor muscle of breath” but is essential to many other processes affecting well-being.4 These include “expectoration, vomiting, defecation, urination, swallowing, and phonation.” In addition, these authors pointed out, the diaphragm influences the body’s metabolic balance; stimulates venous (blood on its return to the heart and lungs for oxygenation) and lymphatic return, “thereby creating the correct relationship between the stomach and the esophagus to prevent gastroesophageal reflux”; is essential for posture, locomotion and upper limb movement; influences “the emotional and psychological spheres”; and can diminish the perception of pain.

The third reason that a focus on breathing can make a profound difference in well-being is that, in our twenty-first-century culture, the activity we call “breathing” is basically ignored. For most of us, breathing is an automatic function, that is, it runs without conscious involvement. It’s on automatic pilot. You think, “This is great; one less thing to deal with.” However, the lack of attention to breathing creates rapid, high chest breathing with little diaphragmatic movement, which negates all the benefits mentioned above. So, when you start to pay attention to your breathing and learn how to breathe efficiently, the payoff can be big. And when you focus on an active, spine-stretching outbreath and a passive, relaxed inbreath, the payoff is enormous.

No matter which breathing method you use, when you focus on breathing, there are benefit. For two reasons, however, I advocate the approach known as the BreatheOutDynamic system (BODs), developed by an Olympic trainer.5 First is its efficiency, generated by a focus on the active, spine-stretching outbreath for energy and relaxation. The inbreath, on the other hand, is short, passive and relaxed—it happens all by itself, if you allow it. This is the opposite of “regular” breathing. The second reason I champion BODs is because it supports physical activity—as well as management of anxiety, fear, pain and stress, all without drugs.

RECOGNIZE MOVEMENT AS A HUMAN IMPERATIVE

The human body is designed for movement, whether it is movement of air and blood, arms and legs, food and drink, the bowels or urine. And breathing is the foundation of all movement.

For the purposes of this article, let’s focus on the movement of air, blood and mucus—the contents of the lungs and associated structures. The intricate dance between air and blood begins in the lungs where oxygen is sifted out of air for passage from lung tissue—the alveoli—into the circulatory system with its microscopic capillaries surrounding the lungs. Capillaries also facilitate the passage of carbon dioxide from blood into the lungs and then out of the body with an exhale. Our sedentary lifestyle, along with chronic high chest breathing and damaged lungs, have compromised this essential movement of gases.

Josiah Child, MD, chairman of emergency medicine at Los Alamos Medical Center in New Mexico, is a BODs athlete. In my book, Just Breathe Out—Using Your Breath to Create a New, Healthier You,6 I share his explanation of why BODs enhances the body’s ability to welcome oxygen into the bloodstream at the capillary interface and efficiently eliminate carbon dioxide. He credits BODs with his own ability to overcome two embolisms and return to work after debilitating Covid experiences.

To explain the process of oxygen entering the blood, Dr. Child uses the metaphor of a cruet of oil-and-vinegar salad dressing. Unstirred, the lighter oil remains at the top, while the heavier vinegar remains at the bottom. Now picture air instead of oil, and blood instead of vinegar. With a sedentary lifestyle, a static rib cage and lungs are similar to the unshaken cruet. In order for oxygen molecules in the air to join the blood on its journey around the body, oxygen must mix with blood. Air must descend deep into the lungs and blood must ascend in the capillaries that hug the lungs. The inactivity of twenty-first-century life leads to an ineffective mixture of blood and oxygen. The result is low—or no—oxygenation of every organ system, muscle and cell in the body.

Using BODs, the active outbreath and passive inbreath create the vacuum/suction that promotes efficient and effective mixing of air and blood. This simple switch in practice can overcome many of the pitfalls of sedentary living. And when BODs is coordinated with movement—including rising out of bed, activities of daily living, making love, daily exercise routines and sports—your function improves and anxiety, fear, pain and stress diminish.

HYDRATE AND EAT, WISE-TRADITIONS-STYLE

Water, essential to all life, keeps normal processes functional. How do you determine your daily intake? The modern-day recommendation is to drink six to eight eight-ounce glasses of water every day. But plain water can also deplete the body of minerals. It’s best to add a quarter teaspoon or so of unrefined salt to an eight-ounce glass of water; other good sources of water include salted broth and soup, raw milk and lacto-fermented beverages. And let’s not forget “metabolic” water, which is formed right in the cells when we metabolize fats. Those who consume a high-fat diet don’t need to drink as much water as the experts recommend.

HANDS-ON RESPIRATORY THERAPIES

Outbreath-focused breathing promotes the movement of air out of and into the body, as well as the movement of air and blood within the lungs and into blood circulation. Another substance in the lungs needs to be kept on the move. It is mucus—the sticky, slimy, essential substance that lines internal body surfaces. In the lungs and airways, mucus moistens, lubricates and protects the body from unwanted particles and chemicals.

While excess mucus is generally not an issue with pulmonary fibrosis such as that observed with long Covid, it is important to keep all mucus thin with adequate hydration and other supportive techniques. These include effective focused breathing; huff coughing; clapping (also called percussion); postural drainage; and vibration.

Coughing can wear you out, and rhythmic huff coughing can replace it. A huff is a soft, quick outbreath, through mouth or nose. This belly-force of exhaled air assists the microscopic hairs called cilia to move mucus up your airway, and preferably into your mouth. But the mucus might slide into your stomach where it will be processed.

Clapping (percussion) is a manual technique of gently but firmly slapping a cupped hand against the ribs, which hide the lungs. This wave of energy—a type of vibration—thins the mucus and can even dislodge it, whether you have a common cold, flu or other issue.7 Respiratory therapy did not “invent” clapping but rather adapted it from the ancient tapping traditions of yoga, tai chi and qigong.8 You can accompany the clapping with huff coughing and your active outbreath, all of which push the mucus from the alveoli into the bronchi for elimination via the mucociliary escalator. One precaution is advised: Do not clap over any implanted device such as a pacemaker.

Your right lung is the place to begin clapping, whether you clap your own rib cage or have a partner do it. Because of the geography of the lungs and the angle at which the trachea splits into the right lung and left lung, the right lung is most often the congested one, so start clapping your right lung while lying on your left side. Your right lung and its airways can then drain the mucus into your trachea for elimination. Be sure to give your left lung some attention as well. With fibrosis, your vibration might not bring up any mucus. That’s okay.

Here’s a quick clapping “how-to”: cup each hand and gently clap or slap each hand on your right ribs, covered with clothing or a cloth, for one to three minutes, as tolerated. Then cough and, if possible, expectorate. Continue clapping wherever you have ribs—under your collarbone, on the lower front, back and side. You can assess the effectiveness of your efforts by the sound of your cough. Sometimes the littlest piece of mucus generates a raucous cough. This therapy can continue for twenty to thirty minutes, one to three times a day. A good tutorial on clapping of both lungs is available at Mary and Peter Frey’s “The Frey Life” channel on YouTube; though they are not medical professionals, their “how to do manual chest PT [physical therapy]” video clearly and accurately demonstrates clapping, vibration and postural drainage.9

Postural drainage, which accompanies clapping, is a means of positioning your body so that lung segments drain into the larger airways that lead to the trachea. Each position facilitates the movement of mucus up the convoluted bronchi, for elimination by swallowing or spitting. Each position drains different lung segments. The basic drainage positions include sitting up straight, lying on the right side, lying on the left side and lying flat. Each of these positions has several modifications, including leaning forward and backward, and with buttocks elevated.

In addition to clapping, there are many other types of vibration (see Resources sidebar, p. 37). Many types—including humming, singing, chanting and “om-ing”—involve your vocal cords, which sit in the trachea and are energized by the vagus nerve. You can also gently shake your body by placing your hands together in prayer position across your chest, then wiggling side to side, experimenting with speed. (It feels like the spin cycle on a washing machine.) This warms your body and moves energy around, which can be very invigorating.

In the twenty-first century, the clinical and home care environments have replaced manual clapping and vibration with various machines, including the cough assist (cough simulator), hand-held percussors and the vest (vibration). While these machines are efficient and can provide patients with a means of managing their own care, hands-on therapy— now almost a lost art—is cost-effective and retains its value in personal health management.

No matter which method of vibration you choose—manual, mechanical or both—be fully focused on the process. Be with your body, visualizing the positive influence on your organs, tissues and cells. Notice sensations, feelings and changes in your comfort level. Keep records lest you forget your hard work and dedication to well-being. Be in praise of your efforts and share your knowledge and experience with the world.

PULMONARY REHABILITATION

With pulmonary fibrosis, the ability to be active in daily routines and exercise can improve with pulmonary rehabilitation. I witnessed this myself decades ago when I managed a pulmonary rehabilitation program at a large New Jersey hospital. The program participants had a variety of disabling lung issues, but even with these limitations, tailored exercise routines increased their ability to care for themselves. A prescribing physician admitted to me that the pulmonary rehab program had improved his patients’ functionality so much that they no longer called him with crises. Anecdotal evidence like this is powerful and motivational.

Movement of solids, liquids and gases within your body is supported by the movement of your arms and legs. Walking—even very slow walking—is the best form of exercise, but if you are unable to walk, exercising in a chair or on a bed is also effective. Walking and other forms of exercise are most beneficial when combined with efficient breathing, such as taught with BODs. With practice, your muscles will understand the new routine of active outbreath and passive inbreath. This outbreath-focused, efficient breathing reduces your work of breathing. The result is that you save and gain energy—energy that you’ve “found” through efficiency.

MAINTAINING OXYGEN SATURATION ABOVE 89 PERCENT

People with Covid-damaged, fibrotic lungs can have difficulty maintaining a normal (95 percent and above) blood oxygen level. In the United States, a saturation below 90 percent usually initiates a prescription for supplemental oxygen therapy via nasal cannula. However, most of the pulmonary fibrosis research about oxygen supplementation is inconclusive in terms of stable improvement of blood oxygen saturation, and there are many unknowns about how much supplemental oxygen may be beneficial. As a 2017 report in European Respiratory Review showed, there is no evidence that supplemental oxygen actually reduces breathlessness in populations with fibrotic lung disorders; at best, the researchers concluded, supplemental oxygen might increase exercise capacity.10 The American Lung Association claims that supplemental oxygen supports organ function in general but provides no evidence for this assertion.11

One major benefit of daily exercise is that it may reduce the need for supplemental oxygen. Well-tuned muscles use oxygen more efficiently than weak ones. With regular exercise, your oxygen saturation may stabilize and even improve, especially if you are fully concentrating on BODs while exercising. Learn to love every minute you are moving your body and breathing efficiently. Additional benefits include reduction of anxiety, fear, pain and stress and increased energy and confidence.

It is important to remember that supplemental oxygen is a drug. As always, buyer beware. If you choose to use supplemental oxygen in order to maintain your oxygen saturation above 89 percent, there are several considerations to take into account. First, with what frequency will you be supplementing oxygen? For example, will it be twenty-four-seven, only for sleep or only with exercise? You must decide what makes sense to you. Being stressed by another daily routine can sap your strength, spirit and oxygen saturation. This is why I recommend efficient breathing, which allows you to be attached to your breath without being tethered to an oxygen tank. Talk with your health care provider and agree on a protocol that works for you. More oxygen is not necessarily better.

The second consideration has to do with the oxygen liter flow. Use the least amount that is effective, depending on your activity level. Request a prescription that allows you to determine the oxygen liter flow within a given range—for instance, two to five liters per minute. Again, oxygen is a drug and should be used judiciously. By combining efficient breathing with supplemental oxygen use, you can reduce your need for extra oxygen. A finger pulse oximeter, which instantly reports how well your blood is carrying oxygen, can help reveal this benefit.

At the same time—and this is the third consideration—do not become a slave to that handy-dandy pulse oximeter. It is not necessary to know what your blood oxygen saturation is from minute to minute. What is helpful is to document your saturation perhaps three times a day, especially before and after exercise, and then adjust the O2 liter flow to maintain a saturation at or above 89 percent. Combine this valuable information with documentation of your emotions and physical comfort, all of which influence oxygen saturation.

HOME REMEDIES

Before modern medicine took over, people had access to home remedies from reliable sources such as elders and grandparents. Generation after generation established the effectiveness of these remedies—the proof being in the pudding. Then, in the twentieth century, drugs stole the show and “evidence-based medicine” supplanted home remedies.

Nevertheless, home remedies still keep many of us from running to “urgent care” and coming home with a high medical bill. In the case of respiratory illness, keeping the airway filter—your nose—clear of excess mucus is essential and easy to do at home. To clear your nasal passages and sinuses, use normal saline (made by mixing half a teaspoon of sea salt in one cup of warm water) in a neti pot, or sniff it directly into one nostril at a time, followed by coughing and blowing your nose.

A naturopath recommended two remedies helpful in clearing mucus from the chest during a cold or pneumonia: onions and mashed potatoes. Slice a chunk of onion and breathe it deeply into your lungs. Place it near your head during sleep. Repeat for a few nights or longer, if necessary.

As for the mashed potato, use one large spud, warm (not hot), per treatment (minus the butter and salt!). This becomes a poultice placed directly on your chest. Lie comfortably on your back for twenty to thirty minutes, covering the mashed potato with a towel to preserve the heat. (You may wish to put a towel underneath you to catch the potato if it slides off your chest during the treatment.) Doing this twice a day for a few days can make a difference. You be the judge, and keep records for future generations. If you have a garden, compost the used potatoes!

WHERE TO START

Of all the information you have just read, the most important step is to love yourself unconditionally. This provides primary motivation for self-care. Self-love is enhanced by efficient breathing, which supports every organ system, muscle and cell in your body. Discover what works for you; then define and refine your healing program. Now you’re ready to focus on the therapies that suit your needs and restore hope for a more functional future. Give your body a large dose of daily healing.

SIDEBARS

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

ALVEOLI: Microscopic, grape-like sacks at the end of the conducting airways, with specialized cells that facilitate the passage of oxygen into the blood.

BLOOD OXYGEN SATURATION: A measure of how well your blood is able to transport oxygen throughout the body, easily measured with a “finger cuff” oximeter. “Normal” is 95 percent and above; “acceptable” is above 89 percent.

BRONCHI: The conducting airways, of diminishing size, that split right and left from the trachea (windpipe) and deliver air deep into the lungs.

CAPILLARIES: Microscopic blood vessels that allow for passage of gases back and forth from blood to lungs to heart to tissue.

CILIA: Microscopic hairs that line the bronchi and wave up toward the mouth.

EMBOLISM: A blood clot that obstructs an artery or lung.

EPITHELIAL TISSUE: Forms the outer layer of the body or is the lining of the lungs, digestive tract and hollow structures. Epithelia characteristically have little blood supply.

FIBROSIS: Abnormal stiffness, caused by scarring of tissue.

IDIOPATHIC: Of unknown origin.

MUCOCILIARY ESCALATOR: The teamwork of cilia and mucus in the bronchi. The cilia constantly wave toward the mouth, and the mucus, with its trapped particles, rides on top of the cilia.

SALINE: Normal saline has the same salinity as body fluid and feels comfortable when used to clean the filter—your nose. The recipe: one-half teaspoon sea salt in one cup of water. Keeps without refrigeration.

TRACHEA (windpipe): Starts where the back of the throat splits into the airway in front and the esophagus in the back of the neck. The trachea extends to the carina, located behind the top of the breastbone. At the carina, the trachea splits into the right and left main bronchi.

NUTRITION FOR HEALING THE LUNGS

The most important nutrient for healing the lungs—indeed healing anywhere in the body—is vitamin A. Vitamin A is the nutrient that tells the stem cells how to differentiate—how to become a heart cell or a brain cell, for example. In the case of the lungs, it is vitamin A that can tell the stem cells to create the alveoli cells, rather than make bronchial cells. Any thickening and scarring rather than normal cell replacement is a sign of vitamin A deficiency. Vitamin A is needed to direct an orderly—rather than chaotic—transition of stem cells to differentiated cells.

Liver (especially poultry liver), cod liver oil combined with high vitamin butter oil or Australian emu oil, butter and egg yolks from pastured animals, and most animal fats supply vitamin A. Remember that vitamin A requires balance with vitaminw D and K2, which these same foods will supply.

The other important nutrient for the lungs is saturated fat. The lung surfactants—those molecules which facilitate the passage of air into and out of the lungs—contain two saturated fatty acids. When unsaturated fatty acids or trans fatty acids get incorporated into the lung surfactants, the lungs will not work properly. For example, numerous studies have shown fewer lung problems such as asthma in children brought up on whole milk and butter. Avoidance of industrial fats and oils—and consumption of plenty of butter, lard and tallow—is essential for long Covid recovery, and indeed for treating any condition of poor lung function.

RESOURCES

POSTURAL DRAINAGE AND PERCUSSION

- “Percussion.” physio-pedia.com/percussion

- “How to do manual chest PT (airway clearance).” The Frey Life, Nov. 20, 2015. youtube.com/watch?v=OAm4pm7ufQc

EFFICIENT BREATHING

- BreatheOutDynamic system. outbreathinstitute.com

TAPPING AND VIBRATION

- Search “brain education/tapping” and “yoqi yoga and qigong” on YouTube.

- Vibration exercise | Body & Brain Yoga Quick Class. Body & Brain TV, May 21, 2014. youtube.com/watch?v=waBUpovCuuE&ab_channel=Body%26BrainTV

REFERENCES

- Vaccination nation: the not-so-long odds of long COVID [timestamp 13:33–14:06 and 27:47–28:45]. 1A Podcast (WAMU/NPR), Jun. 1, 2022.

- Robertson S. What is fibrosis? News-Medical. Net, updated Apr. 12, 2021.

- Kathiriya JJ, Wang C, Zhou M, et al. Human alveolar type 2 epithelium transdifferentiates into metaplastic KRTS5+ basal cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24(1):10-23.

- Bordoni B, Purgol S, Bizzarri A, et al. The influence of breathing on the central nervous system. Cureus. 2018;10(6):e2724.

- https://www.outbreathinstitute.com

- Thomason B. Just Breathe Out—Using Your Breath to Create a New, Healthier You. North Loop Books; 2016, pp. 72-23.

- https://www.physio-pedia.com/Percussion

- Search “brain education/tapping” and “yoqi yoga and qigong” (YouTube).

- “How to do manual chest PT (airway clearance).” The Frey Life, Nov. 20, 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OAm4pm7ufQc

- Bell EC, Cox NS, Goh N, et al. Oxygen therapy for interstitial lung disease: a systematic review. Eur Respir Rev. 2017;26(143):160080.

- American Lung Association. Oxygen therapy: how can oxygen help me? Updated Jun. 16, 2022. https://www.lung.org/lung-health-diseases/lung-procedures-and-tests/oxygen-therapy/how-can-oxygen-help-me

This article appeared in Wise Traditions in Food, Farming and the Healing Arts, the quarterly journal of the Weston A. Price Foundation, Fall 2022

🖨️ Print post

brilliant, wide ranging article